Ecstasy of the Medieval

by Marshall Woodward

When the French poet Francis Ponge worries, “after entangling himself with stones, he became a stone himself”, he conjures that ultimate apophatic experience—transformation from writer into divine subject. Ponge’s metamorphosis is the allure of medieval ekphrasis in the 21st century: time occluded by time itself. The alchemical poet who has turned the material of language into the material of being—simply through sustained attention.

I write about the medieval because it is unbelievable. Medieval sociopolitics and geographies give us a canvas to indict and overlay the present. A past so distant that we don’t worry about insulting anybody—a safe enough, clean enough, mysterious sandbox.

I genuflect to a weirder time, deflect from our modern age, as a way to confront challenging ideas. Because our lives today are unbelievable. Like Bede’s sparrow, we can only know that we are inside some greater hall. Memento Mori, as simple as the remembrance of death sounds, guides us to the unrelenting faith that we are present, briefly, present, briefly, presently gone.

Dante, in eight brief lines in Occitan, mocks the past and departs Italian for a fading Occitan dialect, vei la passada folor, e vei jausen lo joi qu'esper, denan. “I see past folly, and see the joy I hope for, one day.” Dante, and Arnaut Daniel—the Occitan poet he here paraphrases—share Ponge’s anxiety about the metamorphic condition of man, that one day we will not be living cells, but atomized in tectonic plates. That we will be sublimated and silly and a song, a harmony in the subterranean movement of earth. This, then, is the practice of the geologic past imperfect - the Orphic looking back, hoping it will not curse our future.

This essay offers a model of engaging with unlikely, distant disciplines—like the medieval—as a refraction back onto the present self. Premodern subjects are uniquely helpful in accessing difficult material. They too had miscarriages and plagues. They too had despots who obsessed over immigration. They, too, looked back with great anxiety.

How do we balance this interior worry and the practical realities of life? If interiority is the primary goal of many modern poets, as Mary Jo Bang suggests in The North American Review then how do poets orient outwardly themselves in the real, meaty world? Bang offers an externality, a medieval one at that, as a place to find ourselves:

It’s true that I have an active interior life but most poets do. And it’s also true that I become sometimes obsessed with something (The Divine Comedy) or someone (Lucia Moholy)!

And later:

When I was translating Inferno, I did sometimes imagine Dante, and wonder how he might feel about the decisions I was making. There were the very basic questions, like whether he would approve of my decision to forego his terza rima rhyme scheme, which he’d invented specifically for the poem in order to represent the Triune God (Father, Son, Holy Spirit). I also wondered how he might feel about the fact that I was translating his medieval Tuscan Italian into colloquial English. I’d find myself “explaining” my choices to him! Of course, he always remained silent. In time, I realized I couldn’t look to the dead poet for reassurance, I was going to have to be as resolute a translator as he was a poet.

Bang’s translations of Dante relish in a past subjunctive that is both translation and adaptation, an interiority (the palimpsest) revealed through the exteriority (the ur-text). Bang sublimates that intense worry about getting the past right, sublimates it instead to the need to make work communicable in ‘colloquial English’. She looks back with passion at this foundation that Dante laid and said, yes, I must entangle myself with Dante’s old words and emotions and in them I will find some of my own, today.

My obsession is The Met Cloisters. The holy site of medievalism in America holds French architecture, artifacts, manuscripts from the Middle Ages all housed in a Northern Manhattan campus patronized by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and his surrogates. Here, at the locus of a complex American history, I find my interiority: the mythology of medieval America mapped onto myself. Here, a Middle Ages we never had, but somehow like to preserve.

I write about The Cloisters in New York as an enigmatic, historically-rich backdrop where architecture, restoration, patrimony and apocalypse are distant but intimate objects that help me deal with meditations, ruminations, even grief. I am at once Cajun and French, a poisonous plant, an acanthus leaf, dead and alive at The Cloisters. Like Bang, I often worry what The Cloisters curators might think of my liberal adaptations of their old French stones and bones.

What is a modern curator to make of erotic poems where, like Ponge, I entangle myself with acanthus leaves, dragons, medieval bodies? They are all right to worry about how medieval-inspired writing impacts their museum, their old things. There is a necessary irony in looking at old things. Not quite as cruel as ‘laughing at the dead’, but a distance that irony affords when we turn away from the present to the past. A cherry picking of the most interesting parts - the most prescient parts of the past - that leaves the mundane, or the unshareable, behind.

Medieval ekphrasis is a way of seeing the unknowable and writing through it. To cast light upon the ‘dark ages’ by way of gazing into the past. There are the silly and obscure aspects of medieval life - gargoyles, hard-kissed and well prayed-upon books of hours. There are serious objects—tombs, temples, prayer books. But even with our sustained looking, we are overlooking. Making the past useful, commoditizing history for its utility. For me, that utility is in seeing the past as a site of analogous apocalypse.

The Cloisters is a site of end-times ecopoetics and ecstatic transformation. A distinct vantage point to engage with poetry of apocalypse. The Cloisters, begun by an oil scion, John D Rockefeller Jr., who was simultaneously burning greenhouse gasses while preserving sites of the medieval past. What are the poetics and politics of writing about a site made possible by the fortunes of extraction? And who am I, as an arts student in Houston, who receives the majority of funding from institutions sponsored by oil and gas companies? The Cloisters' own relationship to Standard Oil becomes a helpful distancing tool to examine my own privilege in relation to earth burning.

Come too close to the shield of Achilles and you cannot see all of the scenes depicted; stand too far and you fail to see the detail.

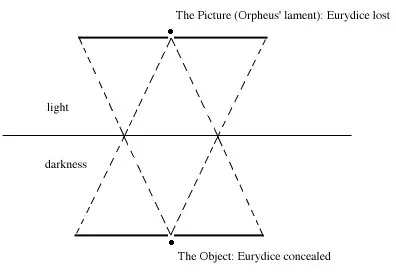

In “The Gaze of Orpheus” Blanchot suggests that turning away from nature is the power of art—that the work of art is “not to see Eurydice clearly; rather, the artist’s job is to bring [Eurydice] back into the daylight and in the daylight give [her] form, figure and reality.” (Quote & Diagram Blanchot, 99) Like Ponge, Blanchot worries about what is real and what is not. The ecstasy, then, is not just the imbrication of the self in the past, but that the present too shall fall to darkness.

In Melissa Range’s “Scriptorium,” Blanchot’s call to figuration is heard through a modern reclamation of medieval butchery. Range’s poem argues an ecopoetics of animal slaughter for the production of text on manuscript—“red calf’s hide” and ink derived from the oak gall wasp’s corpse. Range unites the ekphrastic and ecological by turning to the medieval, a sentimental move made possible by distance.

before Eadfrith’s fingers are permanently stained

the colors of his world—crimson, emerald,

cerulean, gold—outside the monastery walls,

in the village, with its brown hounds

spooking yellow cats stalking green-black birds,

on the purple-bitten lips of peasants

his gospel’s corruption already sings forth

in vermilion ink, firebrands on a red calf’s hide—

though he’ll be dead before the Vikings sail,

and two centuries of men and wars

will pass before his successor Aldred

pierces Eadfrith’s text with thorn,

ash, and all the other angled letters

of his gloss. Laced between the lines of Latin,

the vernacular proclaims, in one dull tint,

a second illumination,

of which Eadfrith was not unaware:

this good news is for everyone,

like language, like color, like air.

The scriptorium becomes the mimetic locus of Range’s poetry. Author and scribe alike are laced between vernacular proclaims, wondering about the red materiality of language, animal blood and golden illumination on the page. The site of writing is also the site of death. Her character, Eadrifth, like Range, relishes in language, color, air, that sustains. They are so much like us, these medievals. Medievals who also hold close their dying, who have already remembered and forgotten.

What are we to do with all the corpses, the stench of death laced in the otherwise ecstatic medieval? Auden offers solace to those overwhelmed by ‘the remembrance of death’—asking the pantheon of “Chaucer, Langland, Douglas, Dunbar” the eternal question “why all age-groups should find our / Age quite so repulsive”. He finds his peers with modcons “beset by every creature comfort” to be bluntly, “so often morose or / kinky, petrified by their gorgon egos.” Genealogy offers security. Genealogy is a cheap trick, one I employ too readily, to establish bumpers and guardrails about one’s poetic lineage, interest and appetite. Auden looks back over his shoulder, like Orpheus,

I would gladly just now be

turning out verses to applaud a thundery

jovial June when the judas-tree is in blossom,

but am forbidden by the knowledge

that you would have wrought them so much better.

Auden dares to peek, wondering, who is back there, are you really there?

Marshall Woodward is a writer and researcher from the Gulf Coast whose work appears in or is forthcoming from Annulet, Antiphony, Fence, The Indiana Review, The Indianapolis Review, postmedieval, The Seneca Review and Waxwing. He recently graduated from the U. of Houston's Creative Writing Program (MFA) where he worked as a poetry editor for the journal Gulf Coast. He is co-director of Space City Medievalism, a project eliciting creative responses to medieval poetry supported by the Medieval Academy of America and The Houston Arts Alliance.